A Tribute from a Ginner-Mawer Student

A Tribute to Irene Mawer by Eileen Stuart (nee Varley)

This week’s blog post is of tremendous importance as it has been written a woman who knew Irene Mawer in person.

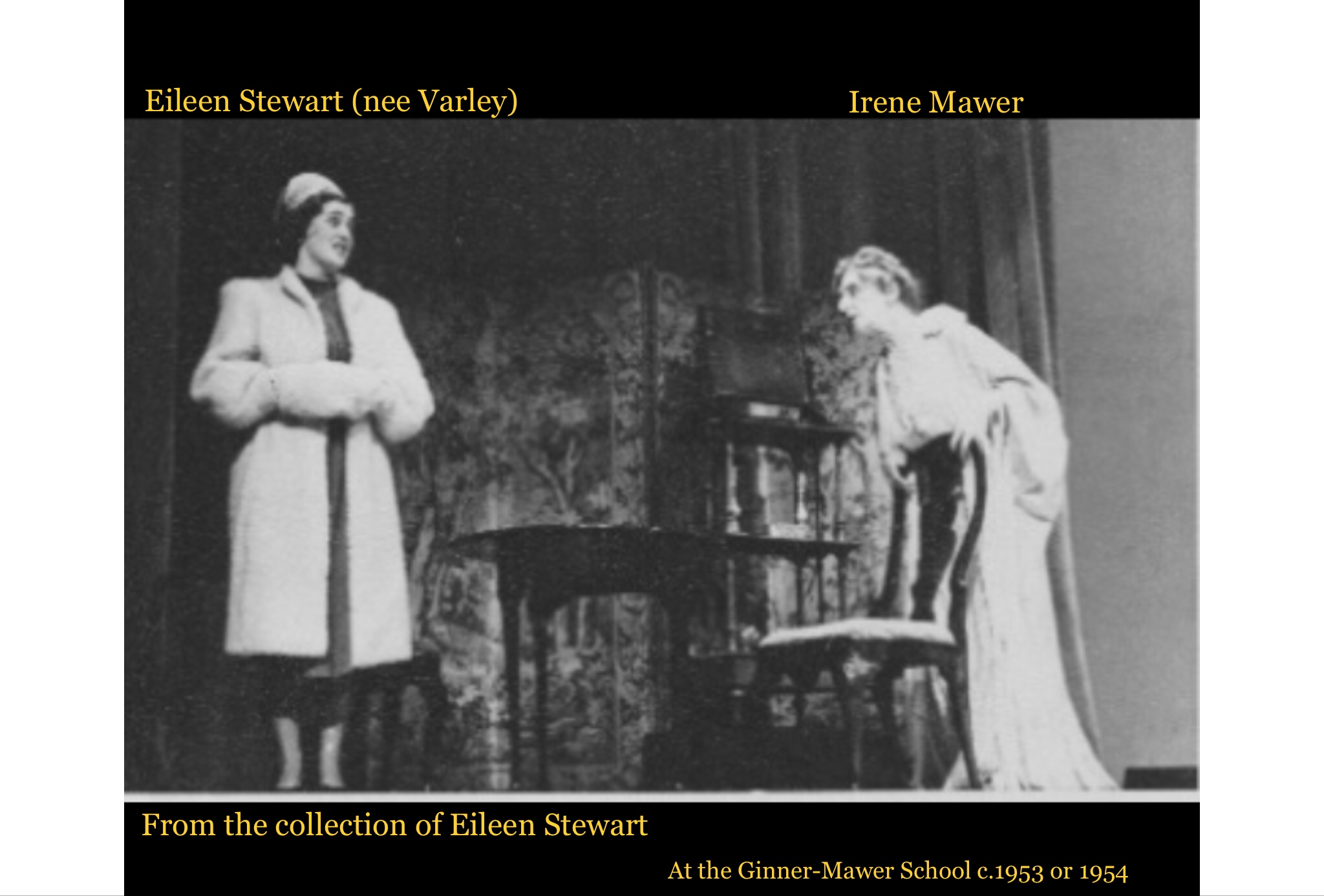

The author of this piece was a full-time pupil at the Ginner-Mawer School of Dance and Drama in the early 1950s, when it was located in Cheltenham.

A Tribute to Irene Mawer

Eileen Stewart (nee Varley) PhD LRAM Dip Ed RSA Dip (Specific Learning Difficulties)

As a sixteen year old girl from industrial Leeds I found myself alone on the train to Cheltenham in the autumn of 1952. My only memorable feature of the journey was the light change so that colour came flooding into the landscape once the train had moved south from Birmingham. A senior art scholarship from the generous City of Leeds Council for three years had made study at the Ginner Mawer School of Dance and Drama possible.

The school was then housed largely in the then faded grandeur of the spa’s Rotunda. As an aspiring actress I had already been involved in radio work from the Leeds and Manchester BBC studios and had dreams of one day appearing at the Old Vic. The Old Vic Theatre School had recently been transferred to Bristol and I would spend the third year of my scholarship there when Ginner Mawer School closed in 1954.

My memories of Cheltenham are now hazy and consist mainly of cycling with painfully stiff calf muscles after my barefoot pounding of the boards at the beginning of each term. However, I am truly delighted that Irene Mawer is, at last, being placed where she belongs for many people – quietly poised upstage centre.

Ruby Ginner undoubtedly dominated the stage most of the time. Her body was by that time large, her personality “pyrrhic”, her upbringing enriched by contacts in the Paris and London artistic worlds. Ruby was immensely proud of her artist brother Charles Ginner and was very like him in her independence of mind and a desire to leave a definite mark on the world through an art form.

Irene Mawer seems to have had fewer background advantages from what Janet has found so far. Her origins were provincial and more firmly within ordinary society. She was, however, highly intelligent, sensitive to theatre traditions but ready to explore new approaches artistically and educationally. Like her new young student she would enjoy dance movement but would never be a dancer.

Both Ruby and Irene had come under the influence of perhaps the greatest pioneer of drama as a force in education and health, Elsie Fogerty – a name that was frequently recalled by both women.

My Yorkshire vowels had actually given me entry into radio drama with Violet Carson playing my grandmother in one family series long before her Corrie fame or before the Archers had been heard of. A regional accent would be no use however in most plays of the time. Irene helped me to change the pitch and shape of those sounds to those of what was then called BBC or Standard English. Her elocution lessons were most valuable to me in the long term, however, in the recognition that the concentration of the mind should be on the precise volume needed for and best use of the acoustic space in which you were speaking. Also the recognition that the whole body and mind were involved in creating sound communication. Strength, it was pointed out, came from the ground upwards and should never be forced mindlessly out from the voice box. The sound you wanted to create originated in the mind. The impetus for it passed through every part of the body which, therefore, needed to be in a state of tonicity like the string of violin but not over tense.

Irene, under Foggey’s influence, had firmly come to the conclusion that all speech was a carefully choreographed form of movement. The idea of speech as vocal music that was as rhythmic and fluid as dance certainly caught my own imagination. I was also alerted to the growing body of knowledge about stammering and its cure. There seemed to be little literature about its causes that I remember at that time and not all the “cures” proved appropriate for everyone. Lisping was another speech “defect” that was currently seen as needing correction. I continued to be interested in this aspect of speech training throughout my life. However, the medical discipline of speech therapy soon took over most of the work that speech trainers had tried to do.

Irene’s empathy with people who had problems with communication showed too in her development of her mime techniques for use in schools. She knew that some children were body shy or found it difficult to communicate their feelings and ideas in words but could tell stories and communicate feeling through mime.

The most important aspect of all this work I believe was her enormous respect for the human imagination and our capacity for empathy.

Irene and Ruby complemented one another therefore. Irene worked from an deeply felt inner experience to an outwardly formulated expression whilst Ruby worked from a much admired existing form to a mental interpretation which brought it to life. Having said this Irene was by no means unaware or averse to making use of the already established techniques and languages of mime. Both women were conscious of tradition and theatrical forms. Neither were, to my mind, artistic rebels though both tried to move those traditions into fresh fields of expression.

By the time the second year of my scholarship was coming to an end Irene had arranged for me to spend my final year at Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. Her perceptive nature had realised that I yearned for the smell of grease paint and that I was by no means ready to become involved in education at that time. However, I never lost the interest I had acquired from Irene for speech problems, or for the dance of words and for theatre history.

I certainly lost interest in the theatre as a career as it moved so quickly into the angry, iconoclastic phase of kitchen sink drama and sexual “realism”. Like Irene I clung on to the joys of the imagination to create and express a life of the spirit that was liberating of positive energy in order to make the world a happier place. This involved, of course, a cathartic awareness of evil and suffering whilst not dwelling in that place persistently. Aristotle’s theory of Greek tragedy certainly linked the imaginations of Ruby and Irene even though they approached the theory from different perspectives. Perhaps their most obvious expression of that common ground was in the production of “The Trojan Women” which I never saw but heard much about from them.

May this website be a means of increasing the appreciation of a truly inspiring and kindly woman and a highly skilled mime.

———————-

From Janet Fizz Curtis: thank you, Eileen, for a very valuable addition to the effort to ensure that Irene Mawer is recognised for her important role in the dramatic arts during the twentieth century. If anyone would like to contact Eileen, please let me know and I will forward your email address.

It is vitally important that Irene Mawer finds her rightful place in the history of theatre arts so please do help the search engines to find her by commenting/liking/sharing, etc. Thank you.

July 2021