Holloway Prison Visit by Irene Mawer

Irene Mawer cared about people. Not only were many of the Ginner-Mawer performances charity fund-raisers, but I think that she in herself was a caring person. Her Great-Niece speaks very highly of the care and attention that Aunt Irene lavished on her young relatives. Money was not in great supply, but love and time were given freely and Aunt Irene played energetic games with the young girls and taught them how to write poetry. Ginner-Mawer student Eileen Stuart (nee Varley) feels that Mawer was the more caring of the two teachers, and describes her as having a ‘warm concern for people’.

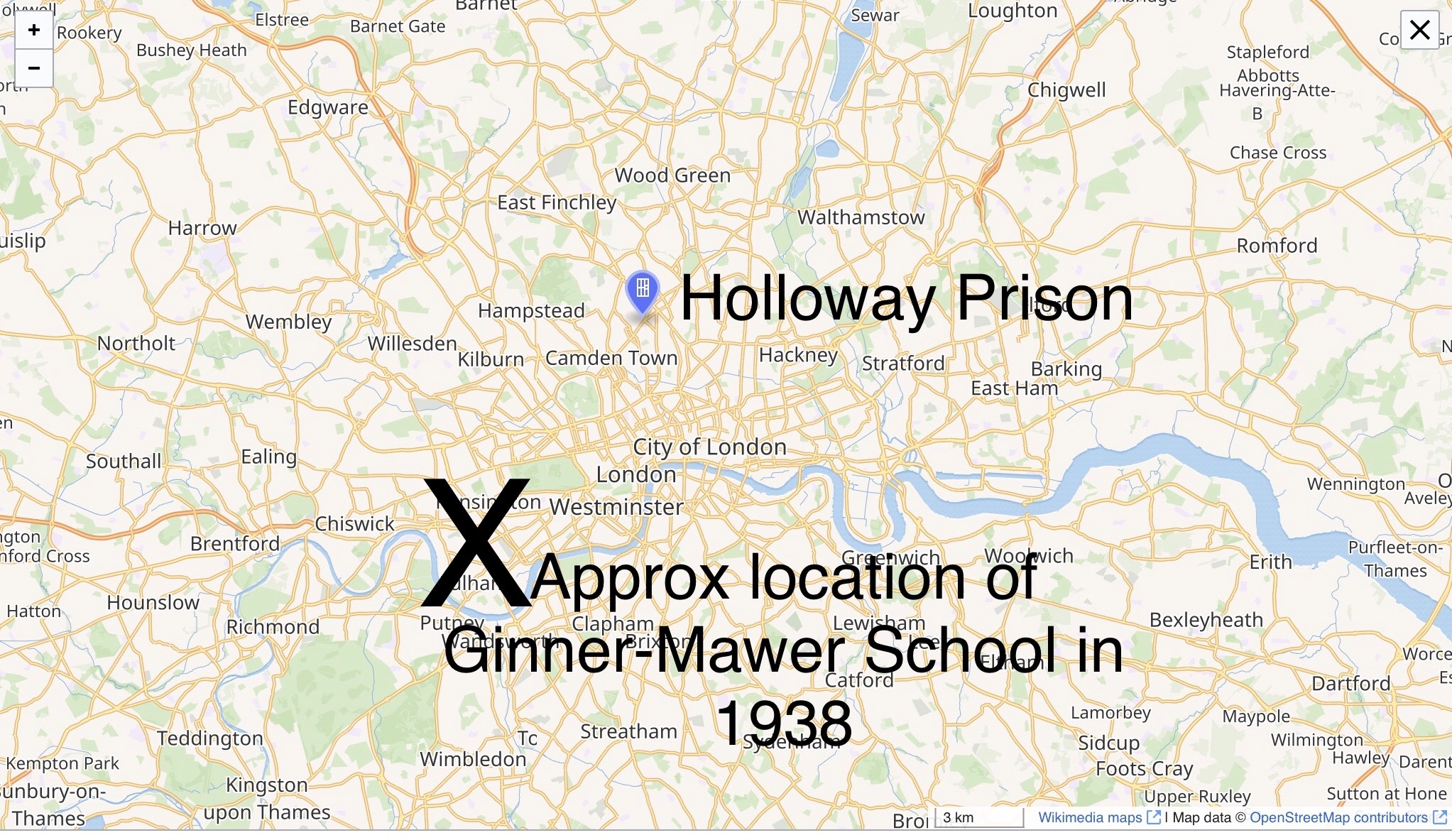

Eileen also notes that Irene was a person deeply committed to releasing creative potential which she saw in others, particularly the women of her era. We can see this in two fine examples of Irene’s work, one branch I have written about previously was with the Women’s Institute (WI), and the second example is from when she visited Holloway Prison – a prison for women. Even today, walking into a prison would be a nerve-wracking experience for anyone – me included. I have been inside Holloway prison, only into the initial rooms, I didn’t go deep into the bowels like Irene Mawer did. Even just being slightly inside a prison was sobering and you can’t help thinking that you hope no-one makes a mistake and that they won’t refuse to let you out. The security is tight, even in the rooms and corridors close to the entrance. The doors lock behind you and you feel a bit scared and certainly apprehensive. So, thinking back to 1938, there would have been very little information in the public domain about what the inside of a women’s prison would be like – no shows such as Cell Block H or Badgirls, no Netflix and no fly-on-the-wall documentaries. Even so, Irene Mawer’s determination to prove that mime could be used as an educational tool took her deep into the middle of a London prison, where she gave a lecture and a demonstration of mime to the prisoners. Here is an excerpt of her description of that event:

“Have you ever been in a Woman’s (sic) Prison? If you have not perhaps the thought stirs in you some kind of sinister apprehension, some feeling of darkness, cold, and uncharitable silence. I confess to some such feeling when I found myself pledged to give a talk and demonstration on Mime to the women of Holloway…

…But my doubts fell away when I was welcomed by kindly courtesy and led into a great mediaeval castle. The noise of the traffic slipped away. It was strangely hushed, but the first things that met my eye were bowls and bowls of fresh Spring flowers, and everywhere colour and light and wam cleanliness…

…a noise of eager voices told us that the audience was gathering. What would they be like; could we give them something that they really needed?…

…I stepped onto the little stage to face an audience that I somehow felt was different from any other I had known.

And what an audience they were! Pale eager faces, many showing an almost spiritual intelligence. And how they loved all we did. I think I have never heard such laughter, certainly I have never known an audience who were so completely with us heart and soul in every movement, every thought. Their quickness to see and to respond made any other audience seem made of clay. I think they loved the handwork best, but everything was appreciated and understood.

When we had finished they gathered round and begged me to come and teach it all to them…

…The friend who organizes the weekly talks for the women said “We have a wonderful hospital. There are so many babies.” Babies born in prison. Flowers and laughter. Strange delicate faces, hardly a coarse one in all that audience. And yet the doors were locked behind us. But they asked us to come back and help them. Can it be that we have found something that will be of use to those brave cheery men and women who build hospitals in prisons…? Something that will last when the doors are unlocked and the women go out into the darkness and the noise of the traffic.”

Holloway Prison was situated in the London borough of Islington, and is now closed. When Mawer visited, she went at a time when conditions were probably at their best and there was a focus on educating the women. So the freshly-painted walls and the flowers were no doubt a result of that forward-thinking. “Humanity and kindness were seen as the best way to rehabilitate. Education classes allowed women to develop new skills…The cells were better lit and ventilated, the building was repainted and flowers were planted in the grounds. Exercise, dining and recreation took place in empty cells and wing basements. New medical staff included midwives and psychotherapists.” (‘Echoes of Holloway Prison – Hidden voices from behind the walls’ published in partnership with Holloway Prison Stories and Middlesex University and Islington Council

https://www.islington.gov.uk/-/media/sharepoint-lists/public-records/leisureandculture/information/factsheets/20182019/20190219echoesofhollowayprison2018.pdf)

Presumably Irene’s previous thoughts on who the prisoners might be had been based on male criminals in men’s prisons – where we can imagine the actors of violent crime and how they might be in the flesh, with aggressive attitudes and intimidating size and strength. Women are capable of violent crime, of course, and of being loud and intimidating and strong, but it is likely that, proportionately, they were in prison for less aggressive crimes. I haven’t been able to find the evidence to back this assertion, though I have tried. If you know any sources that I can use, please let me know. Thanks. Likely to include offences of prostitution, abortion, infanticide (see Lacey, Nicola in Smart 1976, Burman & Gelsthorpe 2017, Peay 2017, Phoenix 2017). Page 137 in ‘Women, crime and character in the 20th century: Maccabaean Lecture in Jurisprudence read 26 October 2017’ in Journal of the British Academy, 6, 131–167. DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/006.131 Posted 26 March 2018. © The British Academy 2018)

Did Mawer carry out her hopes of helping the women incarcerated in Holloway? Probably not – but not through lack of will, but rather because of the location in time and history – because Britain went to war and everything changed, the prison was mostly evacuated, and Mawer herself re-located to Cornwall. “By the 1930s…the limitations of the building itself were restricting progress. Proposals were made to rebuild Holloway in the countryside at Heathrow but these plans ended with outbreak of the Second World War.” (‘Echoes of Holloway Prison – Hidden voices from behind the walls’ published in partnership with Holloway Prison Stories and Middlesex University and Islington Council

https://www.islington.gov.uk/-/media/sharepoint-lists/public-records/leisureandculture/information/factsheets/20182019/20190219echoesofhollowayprison2018.pdf) Like so many plans of so many people – hopes and dreams were shattered and good intentions were left blowing in the wind.